BIG Plastic Had a Choice Between Glass, Aluminum, and Plastic. They Chose Gaslighting

The plastics industry continues to make the ridiculous argument that the best way to lower carbon emissions is to use MORE plastic. The only way to solve plastic pollution is for MORE recycling.

I'm doom-scrolling on LinkedIn and I come across a slick, short video designed to attract my lizard brain. My pupils dilate as they take in the beautiful neon lights and big, bold Helvetica text. Forty-five seconds pass, and I'm now convinced we need to replace all glass and aluminum with plastic.

Wait. What?

I'm easily convinced when my greenwashing shields aren't up. I press a button on my watch, and a fluorescent green bubble surrounds me: greenwashing shields activated. The LinkedIn algorithm has waged war against me, and I'm ready for battle.

A plastic packaging company posted this hypnotic video with an accompanying report. Their findings conclude that plastic bottles have a lower ecological footprint than glass and aluminum. The LinkedIn comments are a cacophony of, "See, this is why we need MORE plastic!"

What is going on here?

I read the report and agree with its conclusions—but I don't agree with the scope. It makes sense that plastic is the best packaging material for a single-use system. I don't have an issue with the findings, but I do have an issue with the industry at large. This report represents an industry groupthink littered with blind spots and heavy with conflicts of interest.

The plastic industry has a convenient and narrow scope. Plastic pollution is always a footnote in the conversation. If it ever gets mentioned, the industry yearns, "If only we can educate the public more about recycling." The only people that need more education are those in the industry itself.

Big Plastic wants us to believe that we need more plastic to save the environment. Stop gaslighting us.

This report, its conclusion, the plastic packaging company that commissioned it, and the plastics industry that celebrates it are all in cahoots to entrench the status quo—one that has led to the climate and plastics crises.

Dear Big Plastic, allow me to provide you with the education you so desperately clamor for.

Reduce, REUSE, Recycling…Single-Use Packages

Recycling = single-use.

Recycling is putting a single-use bottle in a blue bin. Not recycling is putting a single-use bottle in a black bin.

Some (plastic lobbyists) argue (loudly on the internet) that you can reuse a plastic water bottle many times before throwing it away. I argue that they have designed a plastic water bottle for a single use. Reuse is a system, not an individual action.1

The layman thinks that recycling is reuse—that a plastic water bottle will become another plastic bottle—but that’s not how it works. Plastic degrades when it's recycled, which is known as downcycling. A plastic bottle doesn't become another plastic bottle—it becomes carpet.

All plastics have the same fate: they will be burned, landfilled, or littered. Recycling delays disposal; it doesn't avoid it. Only 9% of plastic ever made has been recycled; of that 9%, only 10% has been recycled twice.2

The industry wants a single-use system to be the scope of packaging. It shouldn't be.

Recycling is an inefficient process that's existed for decades but has done little to stop the plastics crisis. Reuse entrepreneurs, big corporations, small businesses, and nonprofits have realized that the recycling system is broken. Instead of trying to fix it, they are creating a reuse revolution. There are over 1,000 reuse organizations globally, and that number is growing.3

This campaign by @grovecollab has made the waste & recycling industry livid. "Plastic recycling is a myth" billboards exist across the US. pic.twitter.com/7hJ4HHYmVA

— Daniel Velez (@VelezD__) June 13, 2022

We've known for a long time that reuse is better than single-use. In 1974, the then-new EPA published a report analyzing the environmental impact of single-use and reusable containers.4 This was their conclusion:

“One basic conclusion that may be drawn from this analysis is that a wide-scale shift from the current ‘one-way,’ ‘throw-away’ container system to a returnable system which maximized reuse and recycling of containers would result in a significant reduction in raw material and energy use, and a decrease in environmental pollution.” - (Hunt et al., 1974)5

When single-use was first introduced in the 1930s, it had several advantages over reusables. Single-use offered a canvas for branding, increased shelf-life, and was available at the, then new, supermarket. Today, the situation is reversed: Reusables have a technological advantage over single-use.6

In the mid-20th century, it was a novelty to throw things away and modern waste infrastructure didn’t exist—thus leading to a littering crisis. A fight emerged between lawmakers and the beverage industry to determine who was responsible for littering.7 Lawmakers wanted the beverage industry to be responsible for throw-away containers. This wasn’t a radical position: the beverage industry was responsible for bottles when reusables were the norm.

After intense lobbying, the beverage industry convinced lawmakers that single-use provides more jobs, that littering can be solved by increasing waste infrastructure, and that recycling is an environmentally sound solution for packaging waste. They also convinced the public that it was their responsibility to stop littering. In other words, the responsibility for waste falls on the consumer and not the producer—a tremendous shift in societal norms.

Just because the beverage industry continues to propagate a single-use system doesn't mean it's better for the environment. More recent studies have reached the same conclusion as the EPA did nearly 50 years. Upstream Solutions' Reuse Wins report summarizes over a dozen studies done in the past two decades that reach similar conclusions: reuse wins.8

There is overwhelming evidence that reuse is better for the planet, but isn't it also obvious? When I go to a restaurant, they don't give me my food on a Styrofoam plate and tell me, oh this is better for the environment. No; they put it on a ceramic plate and wash it afterward.

The transition to reuse has begun, but it isn't at scale yet. Single-use plastics will continue to dominate the landscape. Plastic is light, hygienic, and affordable. In that regard, it is a great material for packaging food. But there are indirect consequences to producing plastic that the industry conveniently ignores.

Indirect Consequences of Producing Plastic

Plastic is a magical material. Its application is widespread and has led to an increased quality of life across the world. Plastic is used in cars, planes, iPhones, spaceships, etc. I'm not arguing for a ban on all plastic. I'm arguing that we need to stop the frivolous practice of using plastic once and throwing it away. We face two severe and urgent global environmental issues because of single-use plastics.

Plastic Pollution

The first issue is plastic pollution. There are microplastics stuck in rotating ocean currents all over the world. The biggest one is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch that is twice the size of Texas.9 These garbage patches aren't filled with glass—we don't call them the Great Pacific Metal Patch—they are filled with micro-plastics that refuse to break down (they were never designed to break down in the first place).

There is plastic in our oceans, national parks,10 fish,11 skin, air, and blood.12 It's everywhere.

Thirty-eight thousand feet in the air, a flight attendant hands a single-use plastic water bottle to a thirsty traveler. Twelve thousand feet below the ocean, the remnants of another single-use plastic water bottle lie on the ocean floor. The fifty thousand feet in between is the only zone in the universe where life exists—and it's filled with plastic. It's everywhere.

Our biosphere is not the only place where littered plastics exist. It's also above us. There is so much plastic debris orbiting Earth that some scientists have dubbed it the “drifting island of plastic.”13 We leave junk after space missions, a terrible inefficiency considering space equipment is absurdly expensive. Elon Musk’s SpaceX bases their entire business model on reusing rockets.14 It turns out single-use is not just an Earth issue—it's literally out of this world.

Climate Change

The second issue brought about by single-use plastic is climate change.

In 2050, plastic production is expected to increase by 30%.15 Oil production is expected to plateau in 2035 and then slowly decline.16 If these predictions hold, we will enter a future where oil is used more for single-use plastic packaging than gasoline—a future that will certainly blow past the 2°C threshold it takes to have a habitable planet.

Plastic comes directly from oil—without oil, there is no plastic.17 Approximately 8% of global oil and gas production feeds the plastic industry and provides energy for its manufacturing. So what happens if we cut oil production in half but use the same amount of plastic? Those numbers would double. Is that a crazy proposition considering that all major car manufacturers are transitioning to electric vehicles?

But what about recycling? Can we use the plastics that already exist to create more plastics?

Recycling Plastic Is a Fallacy

Plastics aren't circular. It takes millions of years for nature to create crude oil—a mandatory element in producing plastic. Humans have existed for 200,000 years. The math doesn't add up.

We can't recycle our way out of the plastics crisis. Even if the world recycled 100% of plastics, we still need virgin oil to create new plastic. On the other hand, glass and aluminum can be recycled infinitely—they don't lose their integrity when they’re recycled.

There isn't an infinite amount of oil in the world, which means that there is a limited amount of time we can use plastics. Considering we use them in cars, planes, and iPhones, you'd think we’d be more conservative with their use.

— Daniel Velez (@VelezD__) June 13, 2022

Only 9% of plastic ever made has been recycled, 12% has been burned, and a whopping 79% is either in a landfill or the natural environment.18 That's 4.9 billion metric tons of plastic either underground, floating in the ocean, in our bodies, or orbiting Earth.

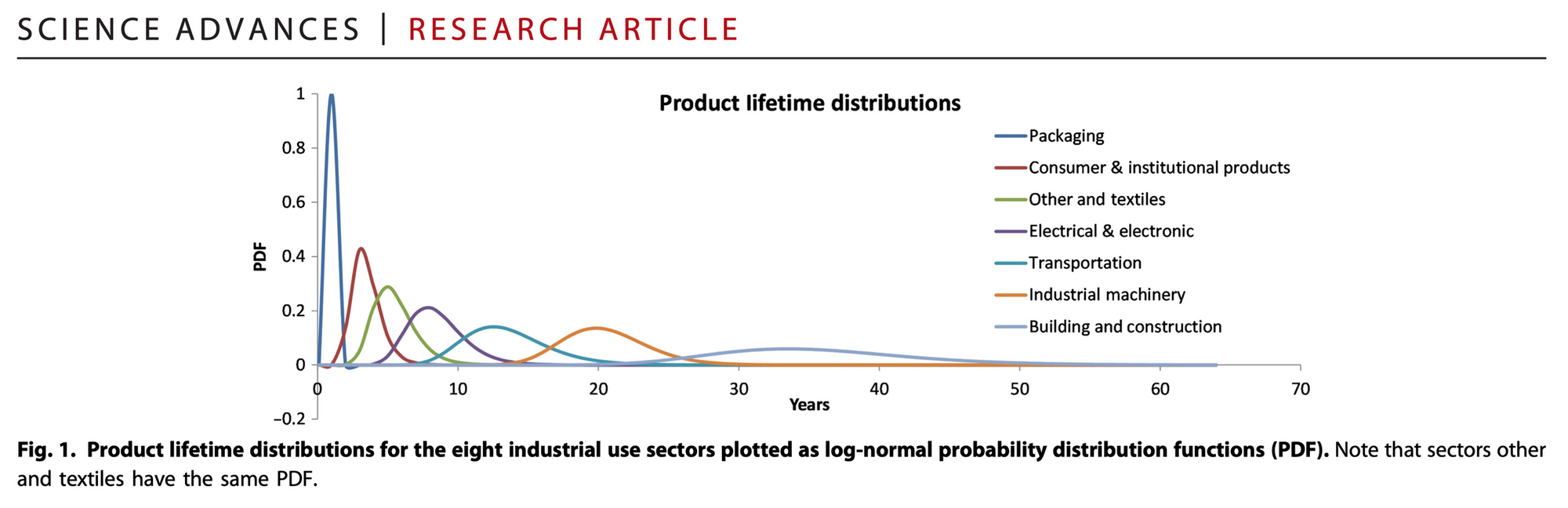

Thirty percent of all plastic ever made is still in use—but it won't be for long. That plastic will have to be replaced by virgin plastic, which requires petroleum to produce. Check out the product lifetime distribution of plastics below:

Although plastics are used in virtually every industry, the overwhelming majority (42%) of plastics are used for packaging. The next largest category (19%) of plastics is used for construction.

The world has done a poor job recycling plastic; but even if we could, we will still need petroleum to produce new plastic. We've had 70 years to solve the plastic recovery Rubik’s Cube, and we haven't done it. Recycling isn't working, but it was never going to work.

Waste management is not a fool-proof system. Littering will occur, especially in countries that don’t have robust waste infrastructure. This unintended consequence needs to be taken into account. Scrappers will at least pick up aluminum litter because it has resale value. Glass doesn’t have value to a scrapper, but at least it's made of biodegradable material and will eventually weather and turn into dust. Plastic has the least value, and when it's littered, it will be there forever.

Not every country has the waste infrastructure of the United States. Even within the United States, rural parts of the country don't have convenient options like curbside recycling. How many of the privileged ones with recycling access are recycling correctly? Recycling incorrectly is worse than not recycling at all because unacceptable items contaminate the recycling stream.

Recycling is hard. The layman will not spend the time to understand the nuances of different plastic recycling in their busy life, no matter how much education they get. I can talk about the nuances of recycling and why it is difficult, but it's not going to change the fundamental fact that recycling plastic isn't sustainable.

We cannot decouple the plastic and climate crises, and recycling plastic will not solve either.

The plastics propaganda machine wants you to believe we should replace all glass and aluminum bottles with single-use plastics and increase recycling rates. This is a catch-22.

Aluminum is the commodity that funds all recycling programs. According to the US EPA, aluminum has always been 3–8 times more valuable than natural HDPE and clear PET—which doesn't include colored plastics.19 Melting different colored plastic together results in black plastic – a virtually worthless commodity. The price of old newspapers is tracked in this EPA report; mixed plastics aren't even mentioned. Next time you're at the grocery store in the laundry detergent aisle, make a note of how many different colors of rigid plastic containers you see.

This shouldn't be news to anybody in the waste and recycling industry. In the late 1980s, many states wanted to pass a mandatory deposit bill which would have created a financial incentive for people to take their bottles back to the store. But, the National Soft Drink Association (now American Beverage Association) argued against it, saying, "If these [aluminum can] packages were not included in curbside recycling programs the operational cost to the municipalities would, indeed, skyrocket."20 In the end, the beverage industry won, and only 1 in 5 states have a mandatory deposit bill today.21

Glass and Aluminum Are Circular; Plastic Is Not

In 310 B.C., ancient Greek philosopher Theophrastus wanted to know whether the Atlantic Ocean flowed into the Mediterranean Sea. He wrote a message in a glass bottle and sent it afloat as a way of testing this theory.22 It's not known what the message said. I don't know if the experiment worked. But, I do know this: glass bottles have been used as a vessel for messages for over 2,000 years, and never during the span of several millennia has there ever been an environmental catastrophe, or a Great Pacific GLASS patch that is ten times the size of present-day Greece.

If Theophrastus wanted to test his ocean current theory today, his glass bottle would get stuck in a gargantuan soup of plastic, resulting in a sulking philosopher sitting on a rock contemplating if his hypothesis was true, false, or stuck in plastic.

There are legitimate concerns with the ecological footprint of glass. When compared to plastic, glass is heavier and requires more energy to make. Unlike plastic, glass can be recycled an infinite number of times, and it will not lose its structural integrity.

So can aluminum.

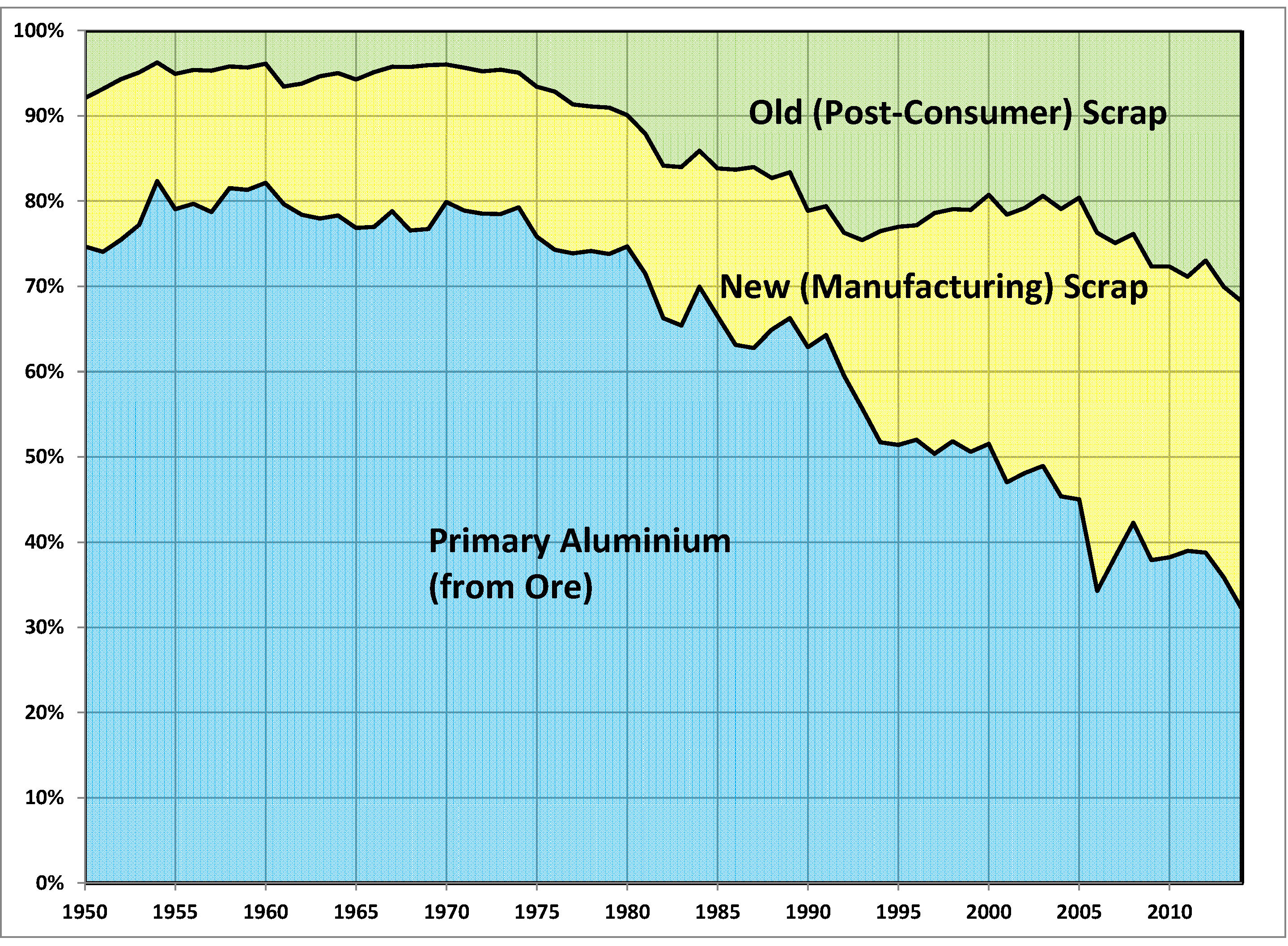

In the USA, more aluminum is made from recycled aluminum than freshly mined bauxite, and it has been trending in this direction for 50 years.

Recycled aluminum takes 90% less energy compared to the primary production of new aluminum. Even so, recycled aluminum bottles, and glass, have a higher footprint than the manufacturing of new plastic bottles. Recycling aluminum and glass requires heating a furnace to melt the material—an energy-intensive process. Doing this every time a bottle is used once is foolish and will obviously have a high footprint. The ethos of recycling is to reduce and eliminate extraction. Glass and aluminum can be melted infinitely into the same quality product. Plastic is barely recycled a second time, does nothing to stop extraction, and is causing an unprecedented pollution crisis.

Conclusion

If we keep doing things the same way, we aren't going to get different results. We are living through two environmental crises that have cascading effects ranging from mass extinction to the disappearance of low-lying islands. Can we afford to keep a single-use model centered around disposable plastic? I think not.

The plastic and packaging industry is taking the position that we need more plastic while ignoring plastic’s dependence on fossil fuel extraction and the substantial plastic pollution. Instead, these industries need to pull their heads out of the sand and innovate around reuse, refill, and the milkman model.

What world do we want to live in? If we choose single-use plastics, we are choosing to overshoot our climate budget and create an uninhabitable world.

Or we can choose a world where glass and aluminum are designed for reusables; and once they can't be repaired, they are recycled into new reusables. A world where we're under the climate budget, where frivolous plastic is a relic of the past. A world that future generations can enjoy.

Enlisting Pirates

Want to take part in a small rebellion? Like my comment on the LinkedIn post that inspired this article :-)

References

1 Velez, Daniel (2022). Confused About Reuse, Refill, and the Milkman Model? Allow Me to Help! Milkman Model. https://www.milkmanmodel.com/reuseterms/\

2 Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3 (7). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700782

3 Velez, Daniel (2022). 4 Resources You Need to Stay on Top of Reuse, Refill, and the Milkman Model. Milkman Model. https://www.milkmanmodel.com/4resources/

4 Hunt, R. G., Franklin, W. E., Welch, R. O., Cross, J. A., & Woodall, A. E. (1974). Resource and environmental profile analysis of nine beverage container alternatives. United States Environmental Protection Agency.https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112105059270

5 Author’s note: Recycling means something different today than it did in 1974. This article mentions an outdated term ‘recycling’ when it actually means ‘reuse.’

6 Velez, Daniel (2022). Reusable Packaging Can Elevate the Customer Experience in Ways Single-Use Cannot. Milkman Model. https://www.milkmanmodel.com/reuse_vs_singleuse/

7 Elmore, Bartow J. (2016). Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism (pp. 255–258). W. W. Norton & Company.

8 Gordon, Miriam (2021). Reuse Wins: The environmental, economic, and business case for transitioning from single-use to reuse in food service. Upstream Solutions. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1opgKG9Xr63-vIT-yTlhMp85-PZz6ltgf/view

9 Meredith, Sam (2018). 'Great Pacific Garbage Patch' has grown to twice the size of Texas, study finds. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/23/great-pacific-garbage-patch-has-grown-to-twice-the-size-of-texas-study-finds.html

10 Treehugger Editors (2022). Get Single-Use Plastic Out of U.S. National Parks. Treehugger. https://www.treehugger.com/get-single-use-plastic-national-parks-5225145

11 Backman, Isabella (2021). Stanford analysis shows plastic ingestion by marine fish is a widespread and growing problem. Stanford News.https://news.stanford.edu/2021/02/09/plastic-ingestion-fish-growing-problem/

12 Snider, Mike (2022). Microplastics have been found in air, water, food and now ... human blood. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2022/03/25/plastics-found-inside-human-blood/7153385001/

13 Marshall, Nilima (2021). Orbiting space debris ‘the new drifting island of plastic’. Yahoo News. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/orbiting-space-debris-drifting-island-150026424.html

14 https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/falcon-9/

15 International Energy Agency (2020). Production of key thermoplastics, 1980-2050. IEA. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/production-of-key-thermoplastics-1980-2050

16 Bloomberg. Demand: Peak, decline and plateau. Bloomberg. https://spotlight.bloomberg.com/story/global-oil-outlook-to-2050/page/4/1

17 Hopewell, J., Dvorak, R., & Kosior, E. (2009). Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1526), 2115–2126. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0311

18 Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3(7). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700782

19 US Environmental Protection Agency (2020). Historical Recycled Commodity Values. US Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2020-07/documents/historical_commodity_values_07-07-20_fnl_508.pdf

20 Elmore, Bartow J. (2016). Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism (pp. 255–258). W. W. Norton & Company.

21 Container Recycling Institute (2021). Redemption Rates and Other Features of 10 U.S. State Deposit Programs. Bottle Bill. https://www.bottlebill.org/images/PDF/Bottle%20Bill%2010%20states_Summary%201.11.21.pdf

22 Pinksy, Clara (2013). Sending Out an S.O.S. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/news/intelligencer/topic/solo-message-in-a-bottle-2013-7/

Milkman Model Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.